The “Does Evolutionary Theory Need a Rethink?” Debate: A Backstory

by Kevin Laland

30 August 2019

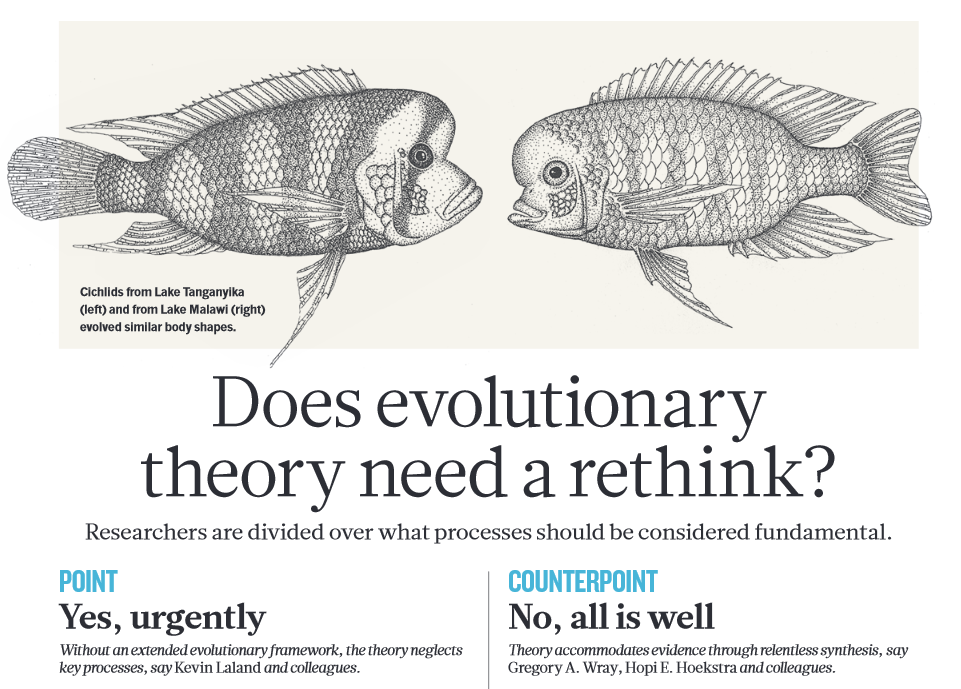

In October 2014, Nature magazine published “Does evolutionary theory need a rethink?”, an exchange in back-to-back articles between advocates of an ‘extended evolutionary synthesis’ and more traditionally minded researchers. The exchange provoked considerable discussion across many academic fields, which continues to this day. Recently, on Twitter, a question was raised concerning the origin of this piece. Who initiated this “debate?” Was there an actual dialogue between the sides prior to publication?

I am not sure if the initial proposal came from researchers or Nature. But it would probably be a good idea to ask the authors themselves.

— Eduardo Zattara (@ezattara) August 15, 2019

Curious, I went ahead and asked. The advocates were led by Kevin Laland, evolutionary biologist at the University of St Andrews in the UK. This blog post came out of our conversations. In this post, he tells his side of the story of how this debate came to take place in the pages of Nature.

— Lynn Chiu (Media and Communications Officer)

Around 2011, Tobias Uller, John Odling-Smee and I pulled together a small interdisciplinary working group to evaluate the concept of an extended evolutionary synthesis (henceforth EES) critically. The initiative was born partly out of frustration. There had recently been a KLI workshop on the topic, organized by Massimo Pigliucci and Gerd Muller, which had attracted a great deal of attention, and the proceedings had been published as an edited volume (Evolution. The Extended Synthesis). However, a lot of fundamental questions remained: What is the extended evolutionary synthesis?, Why is it needed?, How does it differ from the Modern Synthesis and contemporary research in evolutionary biology?, What new findings motivate it?, What are its key assumptions?, What novel predictions does it make? We set ourselves the challenge of answering some of these questions.

The team that we assembled comprised recognized experts in what we felt were the relevant fields, including a leading evolutionary geneticist and member of the National Academy of Sciences of USA (Marcus Feldman, Stanford); two prominent evo-devo researchers (Gerd Müller, Vienna; Armin Moczek, Indiana), including the then President of the European Society for Evolutionary Developmental Biology (Müller); the foremost advocates of niche construction theory (John Odling-Smee, Oxford; Marcus Feldman, Stanford, and myself); leading authorities in non-genetic inheritance (Eva Jablonka, Tel Aviv; Tobias Uller, Oxford); and an eminent philosopher of biology (Kim Sterelny, Canberra). Our enterprise also benefitted from detailed feedback on several drafts from other leading researchers, including Mary Jane West Eberhard (Costa Rica), Marc Kirschner (Harvard) and Doug Erwin (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History).

The working group discussed these issues vigorously over 2-3 years, mostly by email but occasionally meeting in small groups. The team had been assembled on the basis of its expertise, not because they were committed to an extended synthesis. Nonetheless, we rapidly convinced ourselves that spelling out what the extended evolutionary synthesis was – or, at least, could be – would be very useful, for two reasons. First, alternative perspectives can be of value if they motivate research that is unlikely under the dominant view. The EES would earn its keep if it stimulated new questions, generated new answers, and led to new insights into the causes of evolution. Secondly, how people think about biological processes influences the kind of explanations they give. It is often helpful to make these assumptions explicit as it can reduce the risk of disagreement from misunderstanding. Researchers didn’t have to agree with the EES, but once we had specified its core features they would at least know what (some people thought) it was. After much discussion, we pulled together our thoughts and drafted the manuscript that was eventually published as the 2015 Darwin Review The extended evolutionary synthesis: its structure, assumptions and predictions in Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B.

In January 2014 we submitted an earlier version of this manuscript to Nature, who sent it out to review. The editor wrote back to us in March, explaining why they were unable to publish the piece. Of the four referees’ comments, two were glowing (describing our article as “excellent” and “extremely important”) but two were very critical (using terms like “fundamentally unsound” and “wildly overblown” to depict it). This was an early indication of the highly polarized response that the concept of an extended synthesis would evoke.

After reflection, we told ourselves that Nature was probably not a suitable journal for an article of this type. We needed space to make our case in a compelling way – the issues are complex, multifarious and highly technical – and the very short format of Nature articles had meant that most of our evidence and insights has been relegated to an electronic supplement. Accordingly, we started planning to revise our article and submit it to a reviews journal, where we would have more space.

Then, out of the blue, we got a surprise. The editor at Nature got back to us, saying that he had been thinking further about our article, and the divergent responses it had generated in review, and wondered whether we might be interested in participating in a debate. We would be given 800 words to make our case, which would be followed by a response from another team of evolutionary biologists, and the pair of articles would be published in the Nature front matter. The irony did not escape us that, having just been rejected from Nature and reached the conclusion that we needed more space than they afforded to make our argument, we were then given the opportunity to publish there but in far fewer words than our original submission!

Yet it is not easy to turn down the offer of a publication in Nature. We reasoned to ourselves that the Nature exchange would provide us with the opportunity to present our ideas to a huge audience, and would not prevent us from publishing our original manuscript elsewhere, as we had planned. Excited, but not without misgivings, we accepted the invitation.

Writing this short article was to prove more challenging than we envisaged, however. As is standard for front matter articles, we would be allowed no supporting references or figures to make our case, and the article had to be written in a non-technical style to reach a general audience. Moreover, the piece was to be written by a Nature editor on the basis of material that we provided, and not by us – although our names would appear against it. This proved to be extremely stressful. We went through a very large number of rounds of revision of our part (we never saw the response from the others) in which we corrected errors, omissions or distortions that had been introduced, and then the editor re-wrote the piece, but rarely to our satisfaction. Each time we were given just a few days to respond to the next draft – not easy for a team of eight authors with different views (images of herding cats come to mind). This was a complex and nuanced debate, and we were concerned that the article might depict our views too crudely.

A date was set for publication, and as it got closer and closer both the Nature staff and our team became increasing anxious that we did not have an agreed draft. Eventually, a week before publication, when we were still arguing, I held an emergency phone call with the section editor at Nature. She told me that they had long ago finished drafting the response of the counterpoint team, who had given them no trouble at all (!), and that we would have to either accept the final draft or they would drop our piece and publish the response alone.

I was in two minds as to whether we should withdraw our article. We were very conscious of the possibility that a crude representation of the issues could be very counterproductive, and risked alienating the evolutionary biology community. The compromise we reached was that the section editor would undertake one last round of editing herself, which would be the final draft.

With the benefits of hindsight, I think the final draft wasn’t bad given the constraints under which we were all operating. To their credit, the Nature editors managed to write the piece in a way that almost anyone – not just evolutionary biologists – could understand, which was important. The impact of the published piece shows that they did a good job. True, we never felt we had control of the text, and there were some rhetorical flourishes that we didn’t like (“This is no storm in an academic tearoom”), but after all we had been through we were just relieved to have a statement that we could live with.

The stresses didn’t end there. When we got the proofs through the title had been changed at the last minute from our (possibly too prosaic) suggestion Do we need an extended evolutionary synthesis? Yes/No to the snappier Does evolutionary theory need a rethink? Yes, urgently/No, all is well. Unfortunately, this upset both sides. We felt the addition of “urgently” falsely implied that we were desperately unhappy the state of evolutionary biology, whilst a member of the counterpoint team later told me that he felt “all is well” gave the unfortunate impression that they were smugly complacent.

The exchange was finally published on October 9 2014, and it was only at that point that we learned who the counterpoint team were, or what they would say. To this day, I have no idea if they even saw our article before writing their draft – they certainly can’t have seen the final draft of it, since that was completed only a day or so before publication, and after their own piece had been finalized. I can only guess that they were probably fed aspects of our argument by the editors, and had to base their response primarily on earlier publications or interactions. Not surprising, then, some readers feel that the two articles talk past each other a little.

It was frustrating that we didn’t get the opportunity to respond to the counterpoint teams’ remarks – although a protracted exchange in the pages of Nature was never realistic. Nonetheless, it would have let us nip in the bud some non-issues that later came to dominate the discussions. For instance, I have never regarded the EES as a call for revolution or paradigm shift, nor as criticism of the state of the field; it is just another way to think, one that can be useful to evolutionary biologists. These matters are an unwelcome distraction from the important issues with which our field is currently wrestling – rich and fascinating questions, such as how extra-genetic inheritance affects evolutionary dynamics, or whether plasticity-first evolution is plausible. I did write to the counterpoint team after publication to explore whether they might like to continue the discussion, and dig into the debate in more depth, but sadly they had other priorities. That is understandable: these are issues of importance to us, not them.

The Nature exchange was an odd episode in the history of evolutionary biology, but posterity may yet judge it an important one. I still have mixed feelings about it. On the one hand, it probably did polarize the community, and politicize the discussions, to a degree and that is unfortunate. In the aftermath of publication, I was deluged by over a thousand emails from researchers spanning a wide array of disciplines who endorsed our position, many of them sending me publications and manuscripts that they felt strengthened our argument. I’ve had more correspondence about that one short article than all of the other (nearly 300) articles I have published in my career put together! Yet, I know that the counterpoint team received at least as much support, particularly on social media. At the time, none of us on our side of the debate were on twitter or Facebook, whilst the counterpoint team were not only active but backed by traditionally minded researchers with massive followings. It was the realization that contemporary scientific debates are heavily influenced by social media that led us to start the @EES-update twitter and blog (www.ees.dreamhosters.com), as a way to disseminate high-quality research that falls under the EES umbrella.

On the other hand, there is no question that the Nature exchange massively raised the profile of the debate, stimulating a dialogue that reverberated and continues to reverberate around the world. That has to be healthy, and Nature should take credit for seeing and seizing that opportunity. I suspect that without the profile that the Nature exchange afforded, we would never have attracted multi-million dollar grants to address the scientific issues that lie at the heart of the debate. Evolutionary biology has never been more vigorous. Every week exciting new papers on these issues are being published, in which the Nature evolution debate (together with our Darwin Review in Proceedings B) is credited by the authors as a stimulant to their research. Does evolutionary theory need a rethink? has now been cited many hundreds of times, which I would like to think must provide some indication that the ensuing debate ultimately proved useful to the field.

Recent papers:

Laland KN et al. 2019. Animal learning as a source of developmental bias. Evolution & Development. 2019;e12311. https://doi.org/10.1111/ede.12311

Feiner N 2019 Evolutionary lability in Hox cluster structure and gene expression in Anolis lizards. Evolution Letters. https://doi.org/10.1002/evl3.131

Noble DWA et al. 2019. Plastic responses to novel environments are biased towards phenotype dimensions with high additive genetic variation. Proc Natl Acad Sci doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1821066116

Lewens T 2019. The Extended Evolutionary Synthesis: what is the debate about, and what might success for the extenders look like? Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 127(4): 707–721 https://doi.org/10.1093/biolinnean/blz064

Whitehead H et al. 2019. The reach of gene-culture coevolution in animals. Nature Comms 10: 2405 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10293-y

New book coming soon (October 1st):

Evolutionary Causation. Biological and Philosophical Reflections

Edited by Tobias Uller and Kevin N. Laland

A comprehensive treatment of the concept of causation in evolutionary biology.

https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/evolutionary-causation

Find out more about the EES research program at www.ees.dreamhosters.com

Follow us on twitter @EES_update